By Dennis Posthumus

What’s the Story?

In recent months Terra Genesis has been working with Nacozia, a client in the Dominican Republic who is developing a real estate and tourism project informed by a regenerative design process. Tourism can create jobs and lift people out of poverty, but conventional development projects can cause significant harm to the environment, as well as disrupt the economic and social fabric of a place. Together we have embarked on a journey to better understand the social context and cultivate a deep understanding of the landscape.

One of the overarching visions for this project is to create an ecotourism example that can inspire others on the island and model different ways to develop land as it enriches the local culture and economy. What follows is an anecdotal account of the insights that came from developing the beginnings of a regenerative developmental process with Nacozia, from the perspective of walking the project site and experiencing the landscape intimately firsthand.

Context

The Dominican Republic has had the fastest-growing economy in the Caribbean for many years. Increasingly, tourists have been drawn to the pristine beaches, laid-back lifestyle, and kind people of the Hispaniolan island. The country is accessing much of its economic and social potential, which, in many cases of touristic development, unfortunately leads to generic developments and an under-attended consideration of the uniqueness and essence of the place and culture.

However, there is a growing movement of people throughout the Caribbean (including in the DR) who are pursuing innovation and development in both regenerative agriculture and tourism offerings. These alternative developments, which tend to gather around places like Las Terrenas (a small town in the northeast of the island), aim to be more environmentally conscious and socially engaged than a traditional ecotourism example.

Las Terrenas lies on the peninsula of Samaná province. It is part of a unique type of ecosystem called the Haitises, which translates loosely as ‘hills’ in the native indigenous Taíno language, and is the origin of Haiti, the DR’s twin half of the island. The Taíno are one of the original peoples of the island of Hispaniola and form a large part of the roots of its rich cultural heritage. The Taíno called their island Kiskeya, meaning “mother of all lands”, and have been the stewards of the Kiskeyan landscape for centuries. They developed many methods and techniques of working with the environment to create sustainable food production systems, water systems, shelter, clothes, and many other technologies that make their daily lives more comfortable and rich. In fact, the English language contains many words derived from Taíno culture, including barbecue, hammock, canoe, maize, and tobacco; indicative of the depth, relevance, and lasting influence of the culture even in modern times.

As in many other cases in which we seek sustainable and regenerative ways to work with the landscape, we trace back to traditional indigenous methods for vital knowledge and insight. Although we might think that our modern ways are superior, traditional ways have often been developed and honed over centuries of trial and error and, importantly, adapted to the specificity of the local context. That context includes any of the conditions that make a place unique, including climate, geology, flora, fauna, etc. The bioregion of the Haitises has its unique features as well, and understanding those is crucial when we want to evolve a project in the landscape that is appropriate, and builds on the potential inherent to a place.

The Haitises

We completed a preliminary site survey of the property in March of 2022, before undertaking significant landscape design work and research remotely over the next month. We used this time to learn important elements of the area’s ancient history— and current status.

The Haitises form a unique kind of landscape with a high density of conical hills, which are the remnants of precipitated diatoms, marine life, and coral reef beds that formed millions of years ago and have since been eroded by oceanic wave dynamics, receding sea levels, and weathering from rainfall. The geology is predominantly composed of limestone, which in turn gives rise to specific soil conditions, including high porosity and percolation rates.

The particular type of limestone formations in the Haitises lead to what is called a Karst geology, characterized by caves, underground streams, caverns, and other peculiar geological formations such as sinkholes. An ecological consequence of the high porosity of Karst limestone formations is that despite the high amounts of precipitation, plants need to cope with a low capacity of the soil to retain moisture. As a result, it is home to a unique type of tropical forest ecology that tolerates a certain degree of drought, and thrives on calcium-rich high-pH soils.

In reality, much of landscape design can be accomplished remotely, but to actually know and understand a landscape, it is fundamental to visit the site, talk with the community and stakeholders, and cultivate a firsthand experience. Fortunately, we had the opportunity to visit the site with a larger team the following month. This visit would yield crucial insights and emphasized the necessity of physical presence when designing a landscape, and allowed us to confirm and rethink certain design decisions.

Topographical Analysis

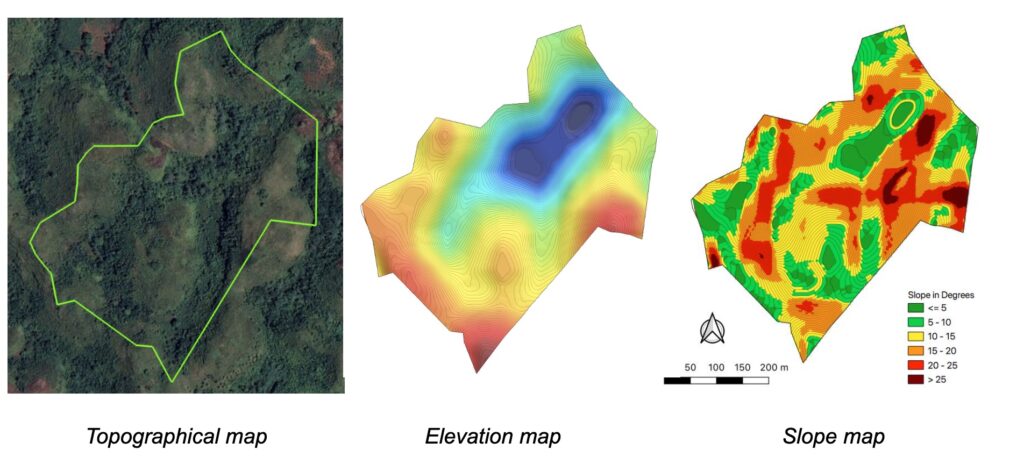

Much of our understanding of the landscape was informed by online research, dialogues with the client and locals, geological surveys, topographical maps, and the plethora of data that are digitally accessible. When we analyzed the landform of the project site from topographical surveys, we quickly noticed the dramatic contrast between steep hills and valleys, with no significant stretches of flat land in between. This is significant because, given that function largely follows landform, the topography of the landscape significantly dictates what we could expect to accomplish.

For example, with the extremes of elevation and lack of flat areas, a focus on annual vegetable production is unlikely. On the other hand, forestry systems thrive on slopes, and play a crucial role stabilizing hilly terrain. To make matters more complex for our context, the project is looking to develop different types of shelter and constructions, which is simpler and more intuitive on flat land, but exponentially more difficult and costly as the terrain becomes steeper.

The various types of topographical analysis we completed in advance of our visit helped shape our understanding of the opportunities and constraints that exist in the landscape. However experience tells that the most meaningful and distinctive discoveries are made while surveying the site, and being physically present. We were looking forward to being surprised, and understanding better what we had missed from just staring at the screen. With all this in mind, I made my way into the hills, along with my colleagues Chris, Øystein, and Robbe– and a Jeep.

Observations

The first major insight of the visit managed to arrive before we did; the path to the land meandered far more than I realized, and made it tougher to access than we had anticipated. I knew from the topographical maps that the access to the land would only be partially tarmac, but I had not considered the extent to which the arrival experience would determine the experience of the place. Clearly, while studying the site on a screen, my focus had zeroed in on the site itself and it would take until I was hurled around in the Jeep and trudging through the brush to recognize the opportunities that arose from a sense of remoteness, and the constraints presented by the difficulty of access

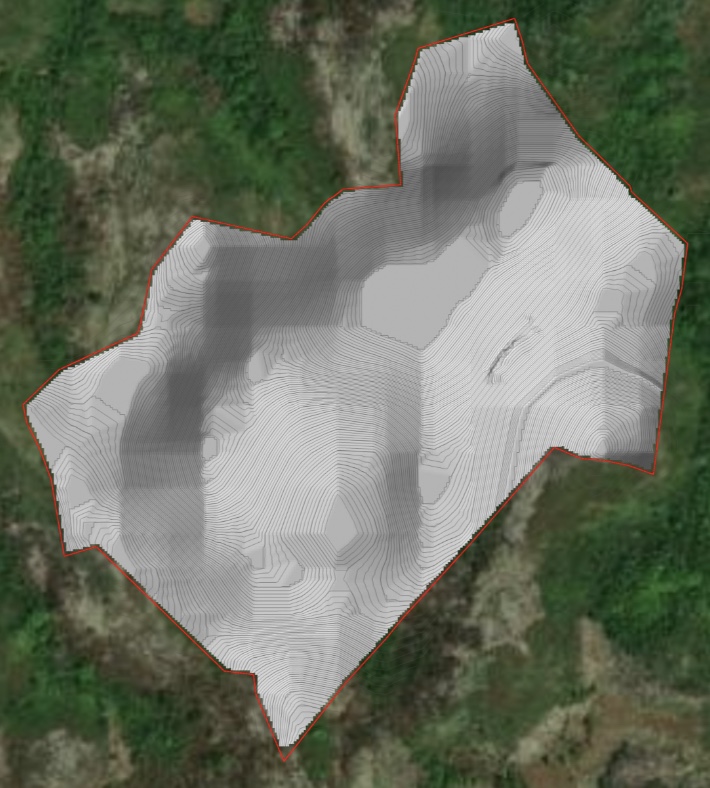

I was struck by a sense of awe from how majestically these 50-meter-tall conical hills rise up from the landscape. The 18-hectare property is a complex of five hills surrounding a central valley that slowly rises southeastward between the hills and transitions into a smaller secondary valley, which wraps all the way around one of the bottommost hills on the property (see image below).

A property this large is obviously impossible to survey in its entirety, or to fully understand in a short amount of time, but I quickly realized that, while we had obviously taken the importance of slope in this landscape into account when creating the initial designs, experiencing the pervasive steepness in this landscape really brought into focus its pivotal role in this landscape. It determines so many things: the experience of place to the functional use of landscape units, the constraints and opportunities for development, the importance of well-graded paths and channeling water flows, and the placement of construction and production areas.

As our walk took us from the valley up to the hilltops, there were distinct zones characterized by varying degrees of humidity accompanied by changes in wind movement. At times it felt like I was wading through hot, still-standing, dense pockets of air, only to emerge from those into higher lying more exposed areas with a persistent cooling breeze. As I walked, climbed, rested, and observed these changes, I couldn’t help being constantly aware of the perpetual interplay between natural factors such as wind, humidity and sunshine, and the shape of the land. This gave rise to a patchwork of microclimates that followed a dynamic patterning process, and these patterns revealed much about how these areas could be experienced and what role they might play in the design of the site at large.

It struck me that even though digital topographical analysis can model and visualize much of the complexity of a site, and lead to rational inferences and conclusions, it is really just a supplemental tool to a much more nuanced process, one that involves being on-site, experiencing the landscape, and being open to let it communicate with the imagination. The senses mediated by consciousness have an uncanny ability to recognize patterns that characterize a landscape, and being on-site in this way leads to profound insights about user experience and the inherent potential that could arise from deepening an understanding of the landscape.

The Stakeholder Pentad Reveals Insights

The site visit sparked interesting and intense exchanges, mostly centered around reconciling the needs of the client with what the landscape is telling us. We sought to understand the role of the project in the context of the wider environment (ecologically, socially, and economically) and worked together to challenge the role that regenerative design and development play in this context.

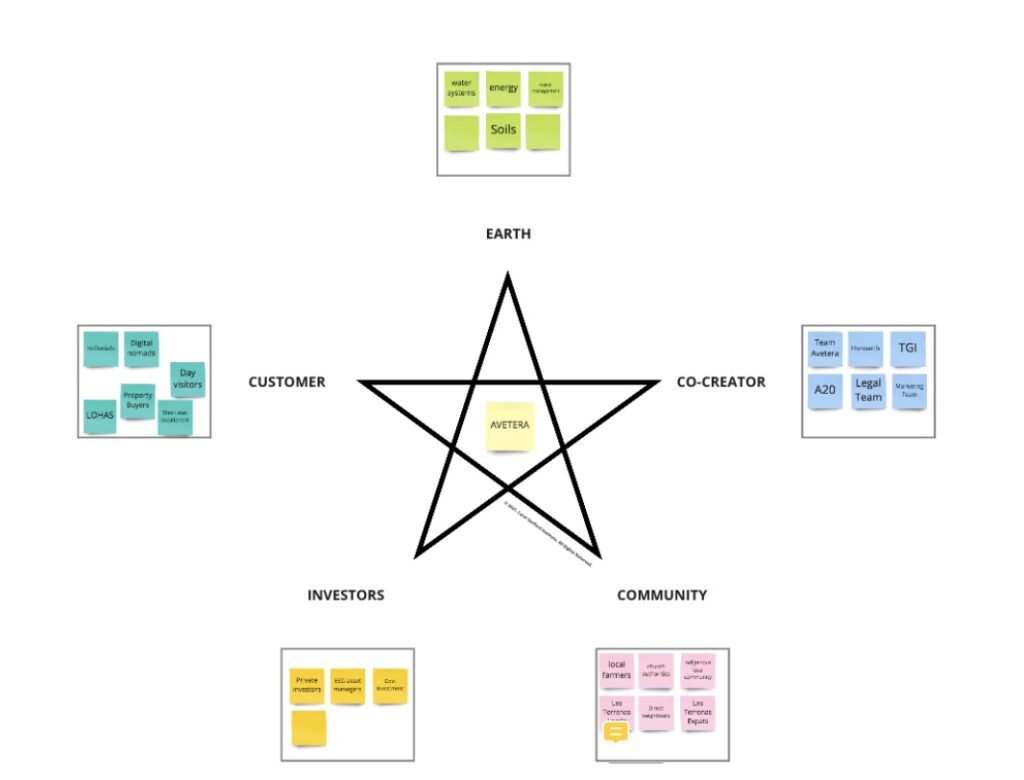

We slowly arrived at a common ground that reconciled all our perspectives, although the process did not end there. In fact, working with a regenerative design process enabled us to recognize that designers and clients are really just two stakeholders in a larger web of actors. The Stakeholder Pentad™, developed by the Carol Sanford Institute illustrates how different stakeholders work together to drive the evolution of a system.

This teaches us that we need to engage and take into account the needs of not only the client, and their investors, but also that of the landscape, all living beings that share life in that place, and the community at large. Understanding the landscape better is a much more complex process than just examining topography, slope, and elevation— it becomes a process of having conversations with many stakeholders, and facilitating a process by which the various points of view can be reconciled into an ongoing synergistic process. Working regeneratively in that sense extends far beyond ecology, plants, soils, and hydrological processes, into a realm that is about playing an active role in evolving social relationships for the benefit of a greater whole.

To that end, part of our work has consisted of a developmental process with our client, to give them the tools to engage with stakeholders in this fashion, to empower them with the ability to co-evolve their project with their community and the environment, and slowly make ourselves redundant in the process. What started out with a landscape design turned into first steps toward community engagement, a shift from thinking about what is wanted to what is needed. Demonstrating that regenerative development is a process of being present, observing, listening, understanding where you are, and how you might integrate in a meaningful way.

Many months later, when we heard that the client had started to engage with the local youth and learn what their aspirations were while trying to understand what role they might play in the community, we felt gratified knowing that we had done our job well.

Regenerative Development

Regeneration is becoming a more and more ubiquitous term, although it’s not always clear what is meant by it. Consumer goods and apparel industries have increasingly included regenerative agriculture in popular discourse in recent years. In a way, regeneration is an old phenomenon with new connotations and relevance. As an old phenomenon, it is part and parcel of the way that people have long been integral to the landscape, have venerated nature as a precious giver of all that humans needed, and stewarded the land. As a new movement, it is part of our journey of reinventing ways to relate with our natural environment, and the communities in which we reside. To accomplish that, we need to be physically present, be responsive with all our senses, and relearn how to see and interact with our environment. We need to engage in conversation with all those involved, including nature, and collectively develop a notion of what it means to regenerate life in the places of our respective little corners of the earth.