By Michael B. Commons

Introduction

In March, 2022, a group consisting of team members from Terra Genesis and VF Corporation had the chance to visit with the farmers who have been leading the way in regenerative rubber-sourcing efforts. We were deeply excited to connect with the people and the forest garden systems in the south of Thailand where the magic had been happening for so long.

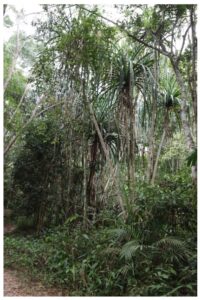

Day 1: Out in the forest gardens, we had the opportunity to connect with and learn from the farmers in rubber agroforestry systems that integrated rubber agriculture with features including hardwood trees, herbs, fruit trees, and even bee colonies. The elements were with us as well, as we found to be true throughout the journey.

Day 2: We began our way to the whole watershed and bioregion of Thale Songkhla by heading to Lad Toey Waterfall in Tamot district. The waterfall and its adjoining forest are managed by the community in partnership with the forest department. I did my best to translate this useful context for anyone nearby, however the voices of the trees, the plants, the birds, and the butterflies needed no interpretation.

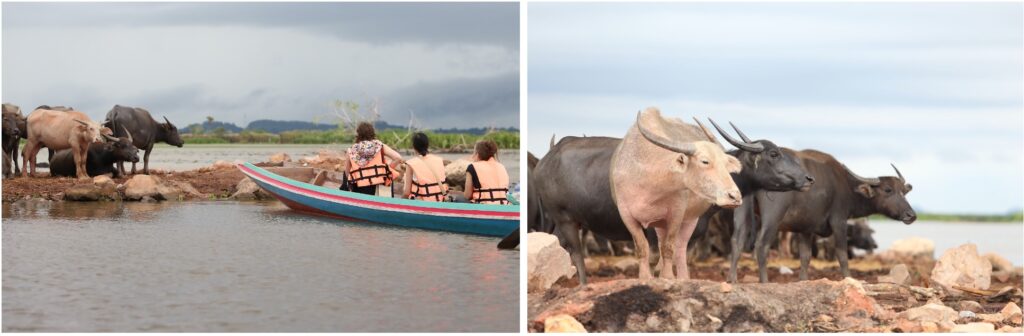

As we approached Thale Noi, our conductors suggested we take cover under the bridge ahead and wait out the dark looming clouds before us. Families of buffalo grazed on the islets nearby, fully in their element. Water buffalo are much loved by Thai people. In fact, they are symbolic of Thai farmers because they historically play a direct and critical role in helping prepare the lands for rice planting.

We opted to make a quick cycle through part of Thale Noi to see some of the beds of waterlilies and abundant waterbirds before heading back to escape imminent showers. We got a proper soaking, as we were not well-prepared with rain gear, but when I finally arrived on the last boat, I discovered the team huddled up in laughter enjoying a drink. The team from VF was truly living the message shared by their brands of getting out into nature, and in touch with the adventure of connecting with each other and the planet.

Day 3:

We were welcomed to the home of Chawapon Omreuang, the former head of Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives for the province of Phatthalung, who has been practicing and studying rubber agroforestry for over 20 years. His in-laws, who he shares the space with, welcomed us with traditional desserts and snacks made entirely from their own organic ingredients and traditional recipes. Then the governor of Phatthalung, who had set a vision to make his province fully organic, and his team joined for some exchange between our parties, under a common vision and goal of regeneration.

After the exchange with the governor, the guests were invited to visit their gardens, including a rubber forest garden, a “Som Rom” fruit forest, and Chawapon’s herd of traditional local variety cattle. In the afternoon we returned to Tamot and were received by Chorthip Prabpree and Vitoon Noosen (who is called Loong Vitoon by those who know him), two amazing farmers whose rubber agroforestry systems are among the most lush and impressive.

In the afternoon, we visited Chorthip Prabpree’s rubber forest garden behind her home, grown on land she purchased herself with the intent to grow a forest. Her courage and initiative to obtain her own land and grow a forest in the way she feels is right gave us a glimpse of the abundance and joy one can find in such a relationship with nature. For example, she ignores conventional ideas of planting ratios and popular conceptions of what may work here or there, instead welcoming in and allowing the plants and trees to teach and show her what they can do.

Next, we visited the farmer elder Loong Vitoon in his rubber agroforest, which is no less impressive. His system is called “Buddhist Way of Farming. ” He explains that at the core, healing the earth and the planet is a journey to heal ourselves, our spirits, and our beings. Thai Buddhist tradition has a long tradition of community members building forest monasteries and spending time in the forest to connect with the Dharma, which has the same root word in Thai as nature (“Thammachat” being the state of dharma). For Loong Vitoon, and other leaders in this movement, connecting with and healing natural environments including forests is key to realizing the truth.

As conscientious consumers, we must ask questions like “what is rubber made from”, “where does rubber come from?” and “where do rubber trees grow?” to understand the impacts from the products we make, buy and use. Exploring the magnificent diverse rubber forests of Chorthip and Loong Vitoon and connecting with small-holder rubber farmer groups, we see very different systems and relationships than that which most people know as “rubber plantations”.

Day 4:

The agroforestry rubber farmers of Tamot hosted a Regenerative Rubber Summit, which was attended by a number of agroforestry farmer groups who joined to share and exchange knowledge, seedlings and products for their systems.

After the opening, four parties ceremonially signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), which expresses a vision and intention of collaboration in support of the transformation of the whole province of Phatthalung to regenerative and organic systems. Those parties included: Thakin University, Phatthalung, which has a long history of research and work on rubber agroforestry; the Governor of Phatthalung, who signed on behalf of the provincial government; Tim Tensen, who, in his capacity as Chief Innovation Officer, signed on behalf of Terra Genesis; and Chorthip Prabpree, who signed on behalf of the region’s rubber agroforestry farmers.

On behalf of VF Corporation, Director of Global Material Supply Jon Hopper shared a message of support for this effort and of the company’s intent to shift the source of key materials, including rubber, to regenerative systems. At this event, we had the privilege to see the key pieces come together under a developing partnership that was building on a farmer-led movement and already activating a wider shift to regeneration.

We tangibly felt that this could spread to encompass this province and watershed with wide-reaching positive effects on the ecology, microclimate, culture, and communities. Throughout the rest of the day, attendees explored these possibilities in speaker sessions, starting with Thailand’s own Jon Jandai, while more informal exchanges continued at different farmer groups’ booths.

The event was punctuated by a Manora performance– a traditional and enduring performing art with a 1200-year lineage. Its story connects to the story of Phatthalung and its watershed. The eponymous Manora are celestial beings that live in the palaces near Songkhla lake surrounded by rice fields and sugar palms. The tradition speaks of 1200 years of abundance from such relationships and care, which has been damaged and degraded, but joins participants together in a movement to heal.

Conclusion

The summit was a point of transformation for many of us, as we were transformed by this occasion of being connected with regeneration as a lived and living experience. The dream of regeneration has been held and practiced by inspiring farmer leaders including Chorthip and Loong Vitoon for many years, but even as recently as when Governor Kukiat began assembling the team and policy needed to transform his province in 2019, there was not the needed support from market or trade partners. Now the farmers and local leaders have seen and met with industry leaders who recognize and value regeneration, and who started to source rubber from these very regenerative agroforestry rubber systems for their product lines. They do so because the world needs this, because their brands help people connect with nature and the planet, and because their customers care. The signing of the MOU represents the fact that all of the pieces are now present and we are working to realize this collective dream of a new kind of rubber industry together.